In recent divagations through the wilds of English vocabulary, I encountered the curious specimen wittol. It turns out that this rara avis is a descendent of a once-vigorous family of terms inspired by the cuckoo and its curious means of raising young. For this week, will will abandon our studies in useful terms that sound much ruder than they actually are, and focus on these linguistic fossils, both living and extinct.

The actual cuckoo and its song was known to both classical and medieval authors for appearing in spring and heralding summer . One of the earliest pieces of written English music, the thirteenth-century pop hit ‘Sumer is icumen in,’ depicts the cuckoo as singing in the season:

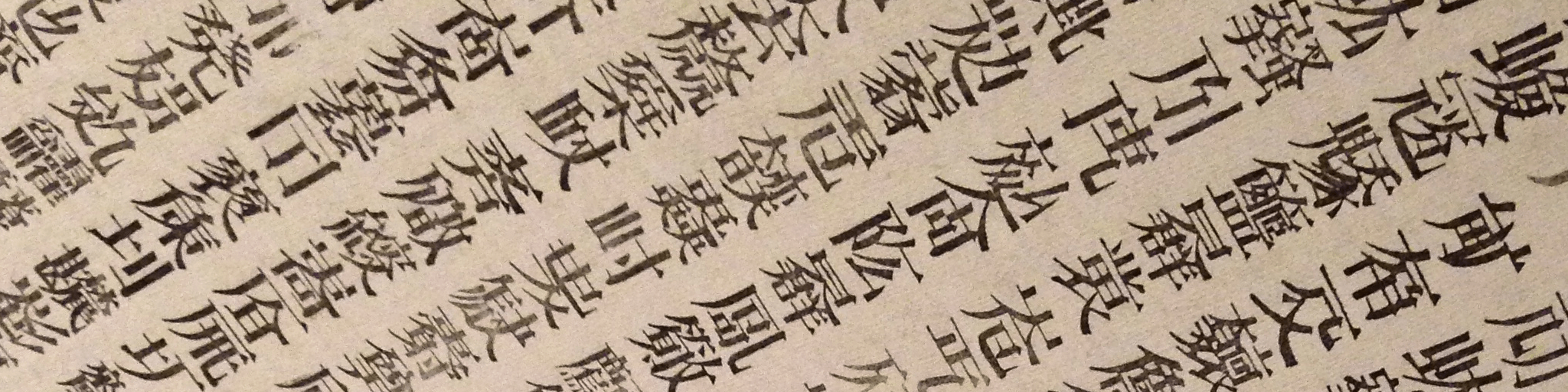

Sumer is icumen in

Lhude sing cuccu …

The cuckoo’s singing is also memorable for its Reichian fascination with its own rhythm, repeated seemingly forever at a stretch. I suspect that this tendency to mindless, maddening repetition gave the cuckoo something of an association with simplemindedness and the compulsions of lunacy, leading to the modern he’s going cuckoo, he’s completely cuckoo, and all kings are cuckoos.

However, it is not the song of the cuckoo that recommends itself to our attention, but rather its fascinating means of reproduction. The cuckoo does not raise its own young. Rather, the female cuckoo lays lays her eggs in the nest of another bird, sometimes making room by eliminating any eggs that happen to be there already. The nest’s owner, being generally bird-brained, raises the young cuckoos as its own, thus saving the cuckoo the trouble of care and feeding. Thus the cuckoo’s nest always happens to be some other bird’s nest, which has led to a an interesting set of associations with infidelity among human couples.

Although it is the male cuckoo that sings, and the female that invades the nests of other birds, when this pattern of homewrecking is applied to humans, we find that it is the male that takes on the role of invader. A man who seduces a married woman cuckolds her husband, who is considered a horned cuckold forevermore. This identification of the male adulturer with the female cuckoo is an interesting reversal of sex, but the implications for the human woman are unfortunate: she is reduced to a passive role as the site of the invasion.

There is in fact a strain of Scottish bawdry that makes very clear exactly what the cuckoo’s nest is and where it can be found, which is perhaps a little too raw to explore fully in a feature of wide circulation. This is regrettable, because the various versions of the air ‘The Cuckoo’s Nest’ are extremely pleasant to sing on a summer’s night:

There’s a thorn bush in the garden where the lads and lassies meet

For it wouldna do to do the do they’re doin in the street

And the first time I went down there, I was very much impressed

By the rufflin up the feathers of the cuckoo’s nest!

I am happy to report that these songs hold the cuckoos themselves up to some rather pointed criticism, but I digress.

The curious word wittol that started this train of thought refers to a witting cuckold. A wittol is a man whose wife cheats on him, who knows that she cheats on him, and who doesn’t happen to mind. It may be that he is a cuckoo himself in his spare time, as well as a cuckold, but at any rate his marriage would appear to be happy enough.

A woman whose husband cheats can be referred to as a cuckquean, though it seems something of a stretch. So strong is the association of the wandering (female) cuckoo with the wandering human male, that in order to reverse the roles cuckoo is explicitly feminized with quean, a woman. This term appears to be completely extinct, whereas cuckold can still be encountered in the wild from time to time, although it is most likely to be seen by moderns in Shakespeare.

Taken on the whole, I cannot approve of the behavior of either cuckoo birds or cuckolding apes. Life is difficult enough without these domestic betrayals. Cuculus non facit magnam felicitatem, sed adulteram. Cave, lector!